Let’s start from the basics: what is pixel-art? And why is it so relevant in the indie game world?

Pixel-art began as a technical limitation from the earliest computers and game consoles, but over time has been “reborn” (not that it was ever actually dead) and established as an art medium in itself, and one of the most characteristic art styles in current indie games.

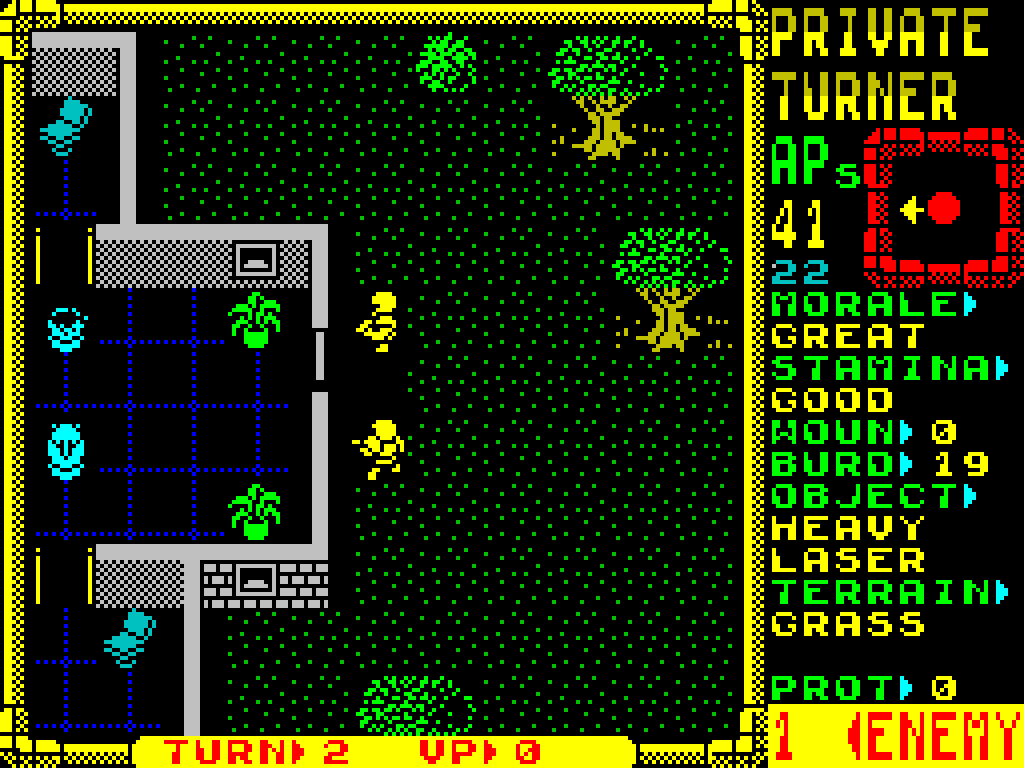

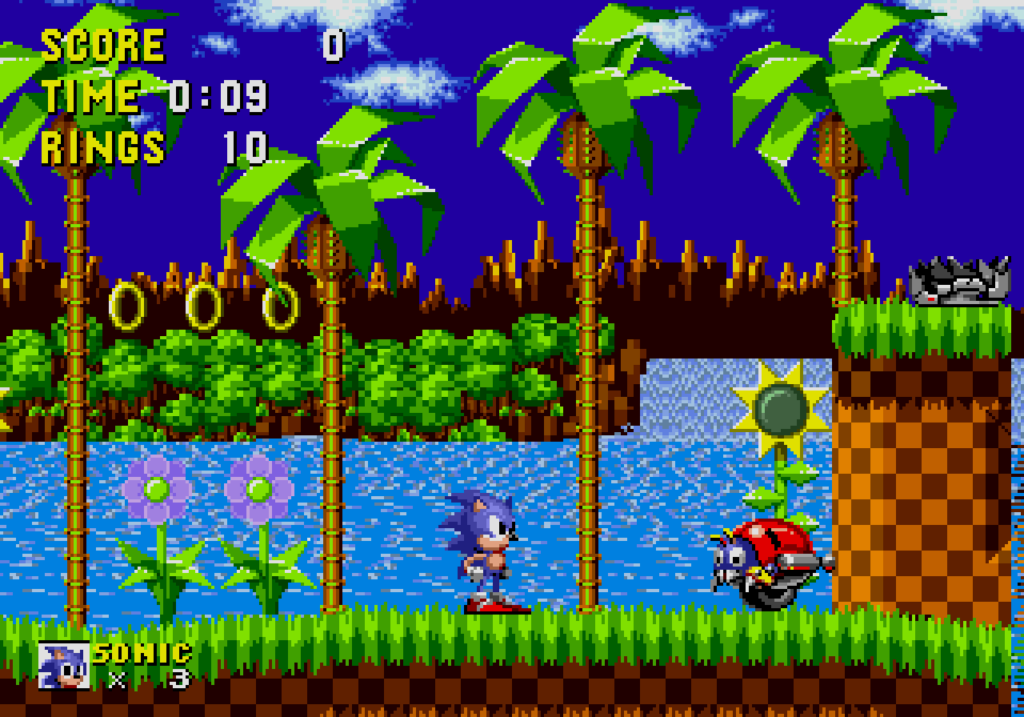

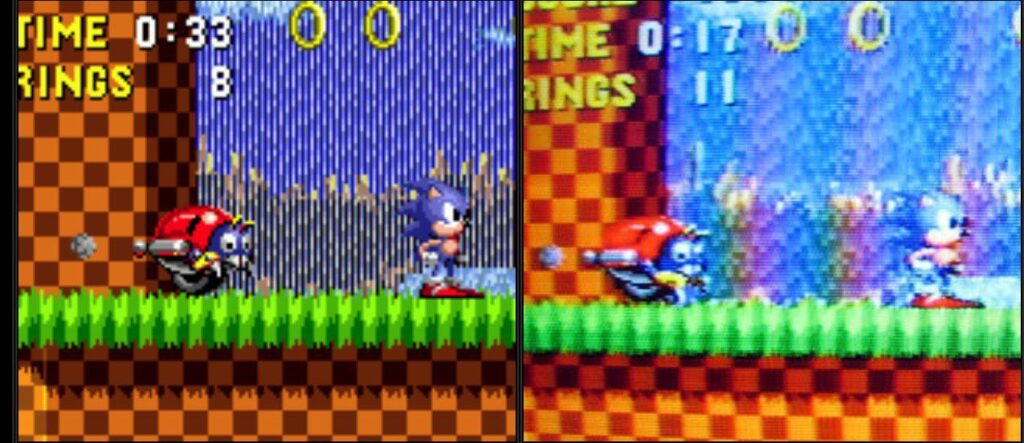

At first, those machines had very low resolution (there weren’t a lot of pixels on the screen), little memory, and could only display a limited number of colors at the same time. To circumvent this, people used techniques not dissimilar to those of cross-stitching or mosaic, where each pixel was placed by hand, taking in mind the palette limitation, to create an “illusion” of complexity. This was aided by the fact that most screens were blurry, or had scanlines, so the pixels weren’t perfectly sharp.

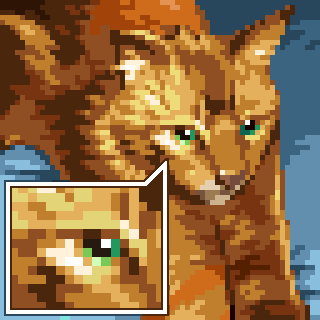

Here’s a pixel-art example, a mosaic example and a cross-stiching example for comparison (source: Wikipedia):

What pixel-art has in common with those other art forms is the use of a minimum unit (a pixel, a tessera/tile or a cross-stitch respectively) that has to be combined with other units in different colors in order to create a picture. These units aren’t seamless, but instead aligned in some kind of grid or pattern. The minimum unit is clearly apparent to the naked eye, even if at the same time it tries to trick it.

That’s perhaps what’s most attractive about these art forms: they engage our imagination because we need to mentally bridge the gap between the obvious pattern and what it’s attempting to convey. We’re always aware of the constraints of the medium and its artificiality, which is what makes it so fascinating and, in many ways, so useful, as we will see.

Nowadays, the screens we use are crisp and defined, and computers can display not only high resolution pictures with thousands of colors, but also advanced realistic 3D graphics. Pixel-art is no longer necessary from a technical standpoint.

Despite this, there has never been a time when pixel-art wasn’t created or used in some form. Back when home consoles and arcades had already made the jump to 3D, portable consoles like the Game Boy Advance and Nintendo DS still used pixel-art in their games. When even portable games made the full jump to 3D, indie games recovered those pixels for a “nostalgia” or retro value and turned them into something new. Nowadays, nostalgia is still a factor, but pixel-art has mostly established itself as simply another way to do art, and in particular to do art for games (although not exclusively: many people do pixel-art for its own sake too, not just for gamedev!). Even the most popular game of all time, Minecraft, uses pixel-art textures for its blocks and models. Pixel-art is a established medium independently from technical limitations and the current console tech race, and it’s here to stay.

A genuine question could be… why? What is so attractive about pixel-art, when much more “advanced” techniques are available today?

Not everyone likes pixel-art, of course. Some are (understandably) tired of it, others just find it too clunky and can’t see the appeal. And that’s fine. Everyone is entitled to their own tastes. However, it’s obvious that pixel-art is still a favorite for a wide chunk of the indie world, both from the creator and the consumer side, and there’s many reasons for it.

The first one would be nostalgia, from the people who remember playing games in those styles when they were younger. Nostalgia becomes a self-sustaining circle, since those creators make new pixel-art games based on the games they played as children, and children today play those games, which in turn may inspire similar nostalgia-driven creations if they become gamedevs, and so on.

However, nostalgia isn’t everything, and in fact I’d dare say that it doesn’t matter as much as we think. Pixel-art is genuinely attractive by itself, for starters: many people who never played pixel-art games when they were younger discover pixel-art later on and show interest in it, because it’s beautiful, clever, or just abstract enough to tickle our brains pleasantly and engage our imagination. Pixel-art has gone beyond a simple technical limitation and has become an art medium on its own merits, and for good reason. It has its roots in perfectly valid and ancient traditions of tesselated, tiled and stitched art, as we’ve seen, and I’m sure that it would have appeared anyway as an art form even if older computers didn’t originally force us to use it for technical reasons.

Thirdly, though, pixel-art is extremely useful and has many advantages, particularly when working with many moving parts, which is common in most videogames. Since you can choose to work with a very small canvas, there’s less variables (pixels) to worry about, which is very useful when you want to make animations, generate variants of the same asset or put different pieces together to create something new. The pixel is the base unit, and since there’s relatively few of them, you can get the wide picture easily and iterate, edit, copy and paste, modify, etc. the moving parts much faster. This is true for characters, backgrounds, tile sets, icons and interfaces.

The main reason that pixel-art has stuck, in my opinion, is not because of “nostalgia”, although that definitely drove its adoption at first, but because it strikes a very good balance between “looks good” and “is fast to create, edit and iterate on”.

Pixel-art is hard to master, but easy enough to learn. Most of all, its accessible, both in its making process (even the simplest graphics editing program allows you to draw pixel-art in it) and the computing power required, since pixel-art graphics and textures take up very little memory and are supported by all hardware or software imaginable. You can make pixel-art on a phone. You can make it on a computer from 35 years ago. You can draw it on a grid paper, like they used to do back in the day, and then transfer it to your computer. It’s the epitome of simplicity and that’s what makes it so powerful and the go-to choice for many indie developers and asset makers.

There’s a reason why precision platformers are usually pixel-art, or why pixel animation is often much smoother and detailed than any other kind of animation in 2D games (setting aside extreme examples like Cuphead). In pixel-art you sacrifice resolution in exchange for control.

So yes, if you’re considering making game assets, be it for your own use or for others, pixel-art is always a good, safe choice. If done well, it not only looks nice, but it can make the game development process much easier.

Thanks for reading! I hope you enjoyed this introductory guide.

Take care,

pingudroid

Leave a Reply